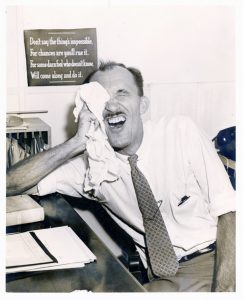

Perhaps the defining moment of scouring through the Albert A. Green archive in the Curious Vault was found on the backside of a 8×10 photo depicting a small device that looks like a vintage keychain mixed with a fishing lure. In flowing script, the photo was labeled: “Shark repellant turned out to be a shark ‘attractor.’” The photo represents a risk taken, a scientific experiment and a failure that appeared to be met with a good laugh.

Albert A. Green wasn’t famous, but the eclectic mass of his life’s work and papers still made it to the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science upon his death. Born right after the turn of the century in Connecticut, Green was a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As an engineer, his story is the standard track for Northeasterners who ended up in South Florida in the middle of the century. He didn’t come for the weather; he came for the war effort.

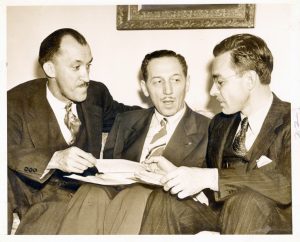

Green spent 14 years working with Sikorsky, an aviation-manufacturing corporation in his hometown state of Connecticut. Sikorsky Aircraft Corp is most famous for inventing and producing the first Army issue helicopter, a project Green was intimately involved with. A framed photo of an early helicopter sits in the archive, signed by Igor Sikorsky the Russian American aviation pioneer, addressed to Green.

In 1942—not long after the United States’ declaration of war on Japan and entry into World War Two—Green moved to Miami to work for the aircraft manufacturer Consolidated Vultee. The archive is an interesting record of a man heavily involved in the aviation war effort. It tells the little known story of Miami’s involvement in the aviation side of strategic operations. In fact, with both the Navy and Air Force operating in such large numbers, many attribute the war as being a major factor in the region’s mid-twentieth century population growth. Around 500,000 Army Air Corps cadets trained on Miami Beach and many of the soldiers returned to make their permanent lives after the war.

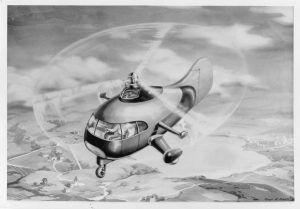

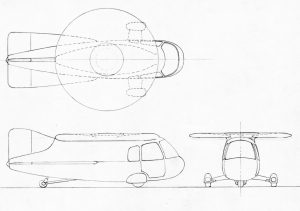

Like the cadets, Green stayed in South Florida and appears to have continued working in aviation engineering. There are countless images of flying machines and helicopters that never quite realized, but were certainly attempted. It’s clear from the materials that Green kept a sentimental place in his life’s work for the helicopter. He bought and donated a helicopter to the local aviation school, which still stands in Miami as the George T. Baker School. In a separate incident, Green and a colleague appear to have crashed a different helicopter somewhere off Miller Road. They were both unhurt, but a 18-inch, dangerous looking, splintered wood and metal shard from the helicopter still remains in the Curious Vault, along with a newspaper clipping from the time describing the accident. Early helicopter experiments were supremely dangerous, as these engineers were charting new ground in flight.

The other objects in the collection are pins from the various jobs he held, but the bulk of the collection is ephemera. There are countless technical blueprints and drawings of highly specialized airplane parts as well as patents filed, won, and never realized. Vast amounts of letters from important sounding mid-century firms that offer substantial sums while pleading with Green to consider moving to their headquarters. The pictures of him, the ones he saved, show Green smiling amongst friends. There is even a hand drawn birthday card signed by his office created with great care.

One letter in particular stands out. Dated February 3, 1961, it was sent from the Office of the United States Air Force Strategic Air Command. It’s an invitation to come and inspect the facilities and fly with the Air Force SAC. A little bit of digging shows that that same date was the launching point of “Operation Looking Glass,” an airborne command center put in place in case of catastrophic nuclear attack on the US that ran until the late 1990s. Obviously Green was seen as an important figure in the aviation world to have received such an honor, and the letter itself is a fascinating bit of militaria with concrete links to a specific top-secret program.

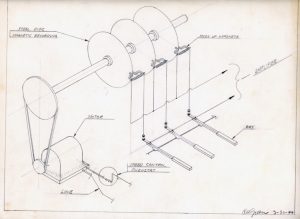

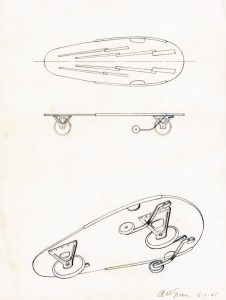

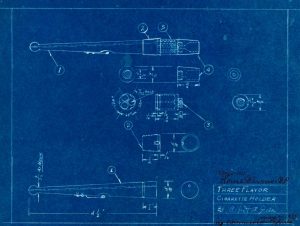

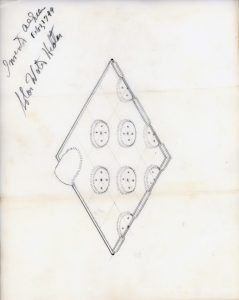

But perhaps aircraft engineering wasn’t everything to Albert Green. Much like the doomed shark repellant, throughout his notes and papers there are countless mentions of other endeavors. Designs for a novelty cigarette filter, an early model skateboard, an electronic music device, and a solar water heater can all be found carefully delineated amongst the notepads and numerous meticulous blueprints. The skateboard and solar water heater are particularly interesting, as they both date from the 1940s and show that Green was a cutting edge thinker.

Sometime around the early 1960s Green left aeronautical engineering and took up a position as an engineer with the construction firm General Development Corporation. Like all good South Florida stories, an eclectic personality eventually ends up in real estate. Albert Green may not have ended up as famous as Sikorsky, or any other aviation figures from the 20th century, but he was an important cog in the greater machine that represents Miami important place in the war effort. His memory lives on in the Curious Vault at the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science, a fascinating slice of oft-forgotten history of the city of Miami.

The Curious Vault is an online cabinet of curiosities featuring objects from the collection of the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science, presented by writer Nathaniel Sandler and Kevin Arrow, Art & Collections Manager. For more information, email karrow@frostscience.org.